[Note: This is the Mishnah Berurah telling you how he thinks the letters should be. If your writing doesn’t look like this, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s pasul. This is not to say that one may arbitrarily ignore parts of Mishnat Soferim, just that other valid opinions as to the letter forms do exist. A student who wants to write differently should choose another style and stick with it consistently. JTF.]

Alef

The upper part has the form of yud, with a little point on it, and the face with the point is turned a little upwards. The leg of the yud should be joined on in the middle of the roof. The right end of the roof should lekhathilah be turned up a little, towards the back. The lower part should be a little wider than the head of the roof, about a quill’s-width and a half. A quill’s-width here is the thickness of the line the quill makes when one writes. On the lower part there is, lekhathilah, a little point downwards on the right, since its form is like that of a yud suspended from the roof of the alef. The point on the left of the upper part is the tag which is on the yud, corresponding to the right point on the lower point. This is what the Beit Yosef says. It follows that the left point on the upper yud of aleph is not strictly necessary, but the Peri Megadim to siman 32, in Eshel Avraham 29, learns that lekhathilah it does have the left prickle like any other yud. If either the upper or lower yuds of alef touch the roof more than in their place, so that the head just looks like a line the same width all through (also the yuds of shin, ayin, peh, tzaddi,), or if the left heads of ayin and tzaddi (which must look like zayin), touch the body of the letter more than they should, they are invalid. He may thicken and lengthen the heads so that they are discernible, and in tefillin and mezuzot only provided he has not yet written anything after them. On fixing by scraping, see the Shulhan Arukh in 32:18. If the upper or lower yuds weren’t stuck to the roof, it is invalid: see 32:25.

The upper part has the form of yud, with a little point on it, and the face with the point is turned a little upwards. The leg of the yud should be joined on in the middle of the roof. The right end of the roof should lekhathilah be turned up a little, towards the back. The lower part should be a little wider than the head of the roof, about a quill’s-width and a half. A quill’s-width here is the thickness of the line the quill makes when one writes. On the lower part there is, lekhathilah, a little point downwards on the right, since its form is like that of a yud suspended from the roof of the alef. The point on the left of the upper part is the tag which is on the yud, corresponding to the right point on the lower point. This is what the Beit Yosef says. It follows that the left point on the upper yud of aleph is not strictly necessary, but the Peri Megadim to siman 32, in Eshel Avraham 29, learns that lekhathilah it does have the left prickle like any other yud. If either the upper or lower yuds of alef touch the roof more than in their place, so that the head just looks like a line the same width all through (also the yuds of shin, ayin, peh, tzaddi,), or if the left heads of ayin and tzaddi (which must look like zayin), touch the body of the letter more than they should, they are invalid. He may thicken and lengthen the heads so that they are discernible, and in tefillin and mezuzot only provided he has not yet written anything after them. On fixing by scraping, see the Shulhan Arukh in 32:18. If the upper or lower yuds weren’t stuck to the roof, it is invalid: see 32:25.

Beit

One must take great care that the letter beit is squared, so that it should not appear like khaf; if it appears like khaf it is invalid. (If one isn’t sure, he asks a child.) It must be squared on the right at both top and bottom; it is not clear what the rule is if the top is round and the bottom square, and it is not proper to be lenient.Lekhathilah it has a little tag on the left side of its head, like a little staff, and a little point upwards on the right side, pointing towards the aleph. (The Yerushalmi in Hagigah asks: Why does the beit have two prickles, one upwards and one behind? They said to beit. Who made you? and it showed them with its upward point. They said to it: What was his name? and it showed them with the point which was pointing back at the aleph, as if to say, One is his name.) It has also a substantial heel below: its form is like that of a dalet standing in the throat of a vav, so it requires a corner above like dalet, and a heel below for the head of the vav. The width and height of beit should be three quill’s-widths, and the width of the space in the middle one quill’s-width.

One must take great care that the letter beit is squared, so that it should not appear like khaf; if it appears like khaf it is invalid. (If one isn’t sure, he asks a child.) It must be squared on the right at both top and bottom; it is not clear what the rule is if the top is round and the bottom square, and it is not proper to be lenient.Lekhathilah it has a little tag on the left side of its head, like a little staff, and a little point upwards on the right side, pointing towards the aleph. (The Yerushalmi in Hagigah asks: Why does the beit have two prickles, one upwards and one behind? They said to beit. Who made you? and it showed them with its upward point. They said to it: What was his name? and it showed them with the point which was pointing back at the aleph, as if to say, One is his name.) It has also a substantial heel below: its form is like that of a dalet standing in the throat of a vav, so it requires a corner above like dalet, and a heel below for the head of the vav. The width and height of beit should be three quill’s-widths, and the width of the space in the middle one quill’s-width.

If one truncated beit so that a child read it as bent nun, one ought to be stringent; see below in the laws of bent nun, also in the Beit Yosef’s second alphabet under vav. I found this explicitly in the Peri Megadim’s introduction, see there; he writes that extending it so that it more properly resembles beit counts as writing out of order for tefillin and mezuzot.

Gimel

Lekhathilah its body resembles zayin (likewise all the left heads of the letters שעטנז גץ resemble zayin), so its head is thick. Its right foot is thin, and descends a little further than the left leg. One does not make this left leg excessively slanted, only a bit. Also, it should not be excessively curved, but should come out straight, and it should be lifted a little towards the dalet. The left leg should be drawn somewhat substantially to the zayin at its side, not thinly, so that its form resembles bent nun. The leg should be short, so as to be able to put another letter close to the head. The head has three taggin on it. If the leg and the foot became stuck together, it is sufficient to erase the leg, as explained in 32:18 in the discussion of scraping the hump of het. The laws of taggin are explained in the end of this siman; see the Mishnah Berurah.

Lekhathilah its body resembles zayin (likewise all the left heads of the letters שעטנז גץ resemble zayin), so its head is thick. Its right foot is thin, and descends a little further than the left leg. One does not make this left leg excessively slanted, only a bit. Also, it should not be excessively curved, but should come out straight, and it should be lifted a little towards the dalet. The left leg should be drawn somewhat substantially to the zayin at its side, not thinly, so that its form resembles bent nun. The leg should be short, so as to be able to put another letter close to the head. The head has three taggin on it. If the leg and the foot became stuck together, it is sufficient to erase the leg, as explained in 32:18 in the discussion of scraping the hump of het. The laws of taggin are explained in the end of this siman; see the Mishnah Berurah.

Dalet

Its roof and its leg must be short, since if its leg is longer than its roof it will look like straight khaf – and be invalidated if a child did not read it as dalet. Lekhathilah its leg should be straight, inclined a little towards the right, and it has a little tag on the head of the roof on the left. One must be very careful to make it square, so that it should not appear like reish and be invalidated by a child’s reading. Lekhathila a corner on its back side is not sufficient, but it should have a substantial heel, so that it would be like two locked vavs; the heel corresponds to the head of one vav and the prickle on its face corresponds to the head of the other vav. If the leg of the dalet is just as long as a yud, it is valid; see the end of letter tav. If one wrote hey instead of dalet, he cannot fix it by scraping off the leg to leave dalet; since it was made invalid and took the form of hey, it won’t work because it will be hak tokhot. Also, he can’t fix it by extending the roof, since anything which does not invalidate the form of the letter counts as hak tokhot. He must scrape back the roof until it has the form of vav and complete it, or remove all of the right leg such that not even as much as a yud remained, and only then complete it [Peri Megadim].

Its roof and its leg must be short, since if its leg is longer than its roof it will look like straight khaf – and be invalidated if a child did not read it as dalet. Lekhathilah its leg should be straight, inclined a little towards the right, and it has a little tag on the head of the roof on the left. One must be very careful to make it square, so that it should not appear like reish and be invalidated by a child’s reading. Lekhathila a corner on its back side is not sufficient, but it should have a substantial heel, so that it would be like two locked vavs; the heel corresponds to the head of one vav and the prickle on its face corresponds to the head of the other vav. If the leg of the dalet is just as long as a yud, it is valid; see the end of letter tav. If one wrote hey instead of dalet, he cannot fix it by scraping off the leg to leave dalet; since it was made invalid and took the form of hey, it won’t work because it will be hak tokhot. Also, he can’t fix it by extending the roof, since anything which does not invalidate the form of the letter counts as hak tokhot. He must scrape back the roof until it has the form of vav and complete it, or remove all of the right leg such that not even as much as a yud remained, and only then complete it [Peri Megadim].

Hey

Lekhathila one makes hey with a little tag on top on the left side, and lekhathilah one should be very careful to make its behind squared like dalet, not rounded like reish, although one need not give it a heel as for dalet so long as the letter has a point. The dot which is inside it should not be close to the roof, but there should be a gap between them such that an average person reading the Torah from the bimah would be easily able to tell that they weren’t connected, and read it as such; neither should it be more than a quill’s-width distant from the roof. If it touches the roof, even if the join were only as thick as a strand of hair, it is invalid, even if a child knew that it was hey – see above, 32:18 and 25. The dot should not be opposite the middle of the roof, but opposite the end, on the left side. If one made it in the middle, it is invalid and must be fixed – that is, it must be scraped off and reinstated at the end. However, if one had written subsequent words and therefore couldn’t fix it in this way because it would be writing out of order, he should scrape the roof back so that it lines up with the leg. In a situation where this too is impossible – if for instance the hey was in the middle of a word, so that scraping back the roof would make the one word into two – it may be ruled valid without fixing [as there are many rishonim who hold that the form of hey is thus; see the novellae of the Rashba and Ritva to Shabbat 103, and the new edition of the Rashba to Menahot 29, and the Ran to Ha-bonei, and the Meiri and the new edition of the Ran to Ha-bonei; it is shown explicitly that they hold the form of hey to be thus]. Now we will explain how to do the dot. Lekhathilah the dot should be thin on top and get a bit thicker below, like a yud, and lekhathilah it should be bent downwards a little, to the right side and not to the left lest it appear like tav. The length of the dot should not be less than that of a yud with its lower prickle, and this is an essential factor even bedeavad – see above, 32:16 in the Rema’s gloss, see the Mishnah Berurah. We must caution scribes about this, as they stumble in it greatly. Even so, it seems to me that fixing is of avail here if a child reads it as hey, even in tefillin and mezuzot, and it doesn’t count as writing out of order; it is like a case where the Peri Megadim was lenient, thus: a straight khaf had been made squared, and he permitted ink to be added. The Peri Megadim (32:33) doubted whether it was necessary to make the dot at its end exactly equal to the right leg – perhaps even if it was completed in the middle of the leg it would be fine provided it was of the minimum size, i.e. as big as a yud – and see above, and also the responsa Binyan Olam in section 54, but even so it seems that we may use a child’s reading to rule leniently; see below regarding reish which was made short like vav.

Lekhathila one makes hey with a little tag on top on the left side, and lekhathilah one should be very careful to make its behind squared like dalet, not rounded like reish, although one need not give it a heel as for dalet so long as the letter has a point. The dot which is inside it should not be close to the roof, but there should be a gap between them such that an average person reading the Torah from the bimah would be easily able to tell that they weren’t connected, and read it as such; neither should it be more than a quill’s-width distant from the roof. If it touches the roof, even if the join were only as thick as a strand of hair, it is invalid, even if a child knew that it was hey – see above, 32:18 and 25. The dot should not be opposite the middle of the roof, but opposite the end, on the left side. If one made it in the middle, it is invalid and must be fixed – that is, it must be scraped off and reinstated at the end. However, if one had written subsequent words and therefore couldn’t fix it in this way because it would be writing out of order, he should scrape the roof back so that it lines up with the leg. In a situation where this too is impossible – if for instance the hey was in the middle of a word, so that scraping back the roof would make the one word into two – it may be ruled valid without fixing [as there are many rishonim who hold that the form of hey is thus; see the novellae of the Rashba and Ritva to Shabbat 103, and the new edition of the Rashba to Menahot 29, and the Ran to Ha-bonei, and the Meiri and the new edition of the Ran to Ha-bonei; it is shown explicitly that they hold the form of hey to be thus]. Now we will explain how to do the dot. Lekhathilah the dot should be thin on top and get a bit thicker below, like a yud, and lekhathilah it should be bent downwards a little, to the right side and not to the left lest it appear like tav. The length of the dot should not be less than that of a yud with its lower prickle, and this is an essential factor even bedeavad – see above, 32:16 in the Rema’s gloss, see the Mishnah Berurah. We must caution scribes about this, as they stumble in it greatly. Even so, it seems to me that fixing is of avail here if a child reads it as hey, even in tefillin and mezuzot, and it doesn’t count as writing out of order; it is like a case where the Peri Megadim was lenient, thus: a straight khaf had been made squared, and he permitted ink to be added. The Peri Megadim (32:33) doubted whether it was necessary to make the dot at its end exactly equal to the right leg – perhaps even if it was completed in the middle of the leg it would be fine provided it was of the minimum size, i.e. as big as a yud – and see above, and also the responsa Binyan Olam in section 54, but even so it seems that we may use a child’s reading to rule leniently; see below regarding reish which was made short like vav.

Vav

The head of vav must be short, no longer than a quill’s-width, so that it should not look like reish. Its leg should be as long as two quill’s-widths so that it should not look like yud, but it should be no longer than this lest a child read it as straight nun. For this same reason it is good to make the head rounded on the right side, so that it should not look like zayin – even though the head of zayin protrudes on both sides, it is still possible that a child who is neither especially bright nor especially dull might read it as zayin and thereby invalidate it. Its face should be level, not slanted, and its leg should be straight and level, not broken in the middle. It is also good for the width to decrease gradually, until it terminates in a point. If the leg of vav is short, so that it isn’t even as long as a yud, it is invalid; if it is slightly longer it must be shown to a child. This is also the rule if the head of vav is long and it looks a bit like reish. If one wrote dalet instead of vav, he must scrape off the whole roof, and possibly the whole leg as well – it’s like the case when one wrote dalet instead of reish, when it is necessary to erase the whole thing; see above, 32:18.

The head of vav must be short, no longer than a quill’s-width, so that it should not look like reish. Its leg should be as long as two quill’s-widths so that it should not look like yud, but it should be no longer than this lest a child read it as straight nun. For this same reason it is good to make the head rounded on the right side, so that it should not look like zayin – even though the head of zayin protrudes on both sides, it is still possible that a child who is neither especially bright nor especially dull might read it as zayin and thereby invalidate it. Its face should be level, not slanted, and its leg should be straight and level, not broken in the middle. It is also good for the width to decrease gradually, until it terminates in a point. If the leg of vav is short, so that it isn’t even as long as a yud, it is invalid; if it is slightly longer it must be shown to a child. This is also the rule if the head of vav is long and it looks a bit like reish. If one wrote dalet instead of vav, he must scrape off the whole roof, and possibly the whole leg as well – it’s like the case when one wrote dalet instead of reish, when it is necessary to erase the whole thing; see above, 32:18.

Zayin

One must be very careful that the leg of zayin not be overly long, so that it not look like straight nun and be invalidated by a child’s reading. Accordingly, the leg should not be longer than two quill’s-widths. Its head must protrude on both sides, so that it not look like vav, it must be squared, and it must have three taggin on its head. Its leg must be straight below it, not broken, and there are some who make the line underneath thin when it starts out, becoming thicker as it goes on until halfway down, and from halfway narrowing so as to terminate in a point at the bottom. If the leg was shorter than it ought to be, the rule is as we wrote for letter vav [from above in 32:16 in the Rema, and also the Peri Megadim advises leniency, as it is sufficient for the leg to be as long as a yud. The Derekh ha-Hayyim in the laws of Kriat ha-Torah and the Shaarei Ephraim conclude like the Shulhan Arukh [that one shows it to a child no matter how long the leg was], and so obviously if it was shown to a child and he didn’t read it as zayin one couldn’t be lenient. This is proved from the Beit Yosef in his second alef-beit in letter vav, see there. It seems that even fixing it would not help in tefillin and mezuzot, because of writing out of order; see 32:25].

One must be very careful that the leg of zayin not be overly long, so that it not look like straight nun and be invalidated by a child’s reading. Accordingly, the leg should not be longer than two quill’s-widths. Its head must protrude on both sides, so that it not look like vav, it must be squared, and it must have three taggin on its head. Its leg must be straight below it, not broken, and there are some who make the line underneath thin when it starts out, becoming thicker as it goes on until halfway down, and from halfway narrowing so as to terminate in a point at the bottom. If the leg was shorter than it ought to be, the rule is as we wrote for letter vav [from above in 32:16 in the Rema, and also the Peri Megadim advises leniency, as it is sufficient for the leg to be as long as a yud. The Derekh ha-Hayyim in the laws of Kriat ha-Torah and the Shaarei Ephraim conclude like the Shulhan Arukh [that one shows it to a child no matter how long the leg was], and so obviously if it was shown to a child and he didn’t read it as zayin one couldn’t be lenient. This is proved from the Beit Yosef in his second alef-beit in letter vav, see there. It seems that even fixing it would not help in tefillin and mezuzot, because of writing out of order; see 32:25].

Het

Het’s two legs are made like two zayins – it is proper for the head of the right-hand zayin to have its top right corner rounded – the zayins should be at most a quill’s-width distant from each other, and they should be joined together with a hump [a sort of roof on the top]. One puts a staff [a sort of large tag] on the head of the left leg, not in the middle. One must take care not to extend the roof of het, and if it is extended it is invalid, and cannot be fixed in tefillin and mezuzah because of writing out of order. This applies only when one made two zayins with a long roof, as this is too slanted to be a hump, but if one made a het like Rashi [a straight het, with no hump on its roof], even if it wasn’t square, it is valid bedeavad even if one stretched it very much. If one made het like two vavs, or like dalet-vav or dalet-zayin, with a hump on top, it is valid bedeavad since making it like this doesn’t change it to the form of any other letter – but even so, if it is possible, he fixes it by scraping the surplus part of the letter such that the hump remains in place. For instance, if a het was made like dalet and zayin, and the hump came to the middle of the dalet, not the end, he could scrape a little away from the dalet until it looked like zayin. But if it was at the end, scraping away from the dalet would divide the letter, and in tefillin and mezuzot no subsequent fixing would be possible, because it would be writing out of order; in this case it may be ruled valid without alteration. If a het made like dalet and zayin or like two vavs was found in a sefer Torah, a different sefer need not be brought out on its account, but during the week any such occurrence must be altered until it has the correct form. Scribes must be warned about this, because the form we gave above for het has its roots in the Talmud, and great rishonim stood by it. Know also that bedeavad if one made het with only the staff or only the hump it is valid. R’ Akiva Eiger, in his novellae, decided that het was valid bedeavad even if it lacked both hump and staff – that is, a straight het like our hets – but if it wasn’t too difficult, one should add a staff because this is the lekhathilah way. If the leg of het was broken and only as much as a yud remained, this is sufficient, both for the right leg and the left leg [Peri Megadim in the introduction, where he wrote that it seems to him that this is the rule for all the other letters, etc; there he specified the right leg, but that is because most letters have a right leg]. See what we write at the end of letter tav. If the hump of het wasn’t attached to the het, but the break wasn’t plain to see, it may be repaired even in tefillin and mezuzot, and this doesn’t count as writing out of order [derived from 32:25; see there], but if it was plainly visible, it no longer counts as het. If only one side of the hump was detached from the hey, it is possible that we may be lenient and allow fixing, even if it is plainly visible; see the Beur Halakha.

Het’s two legs are made like two zayins – it is proper for the head of the right-hand zayin to have its top right corner rounded – the zayins should be at most a quill’s-width distant from each other, and they should be joined together with a hump [a sort of roof on the top]. One puts a staff [a sort of large tag] on the head of the left leg, not in the middle. One must take care not to extend the roof of het, and if it is extended it is invalid, and cannot be fixed in tefillin and mezuzah because of writing out of order. This applies only when one made two zayins with a long roof, as this is too slanted to be a hump, but if one made a het like Rashi [a straight het, with no hump on its roof], even if it wasn’t square, it is valid bedeavad even if one stretched it very much. If one made het like two vavs, or like dalet-vav or dalet-zayin, with a hump on top, it is valid bedeavad since making it like this doesn’t change it to the form of any other letter – but even so, if it is possible, he fixes it by scraping the surplus part of the letter such that the hump remains in place. For instance, if a het was made like dalet and zayin, and the hump came to the middle of the dalet, not the end, he could scrape a little away from the dalet until it looked like zayin. But if it was at the end, scraping away from the dalet would divide the letter, and in tefillin and mezuzot no subsequent fixing would be possible, because it would be writing out of order; in this case it may be ruled valid without alteration. If a het made like dalet and zayin or like two vavs was found in a sefer Torah, a different sefer need not be brought out on its account, but during the week any such occurrence must be altered until it has the correct form. Scribes must be warned about this, because the form we gave above for het has its roots in the Talmud, and great rishonim stood by it. Know also that bedeavad if one made het with only the staff or only the hump it is valid. R’ Akiva Eiger, in his novellae, decided that het was valid bedeavad even if it lacked both hump and staff – that is, a straight het like our hets – but if it wasn’t too difficult, one should add a staff because this is the lekhathilah way. If the leg of het was broken and only as much as a yud remained, this is sufficient, both for the right leg and the left leg [Peri Megadim in the introduction, where he wrote that it seems to him that this is the rule for all the other letters, etc; there he specified the right leg, but that is because most letters have a right leg]. See what we write at the end of letter tav. If the hump of het wasn’t attached to the het, but the break wasn’t plain to see, it may be repaired even in tefillin and mezuzot, and this doesn’t count as writing out of order [derived from 32:25; see there], but if it was plainly visible, it no longer counts as het. If only one side of the hump was detached from the hey, it is possible that we may be lenient and allow fixing, even if it is plainly visible; see the Beur Halakha.

Tet

The right head is slightly bent inwards, but not hugely bent. The left head resembles zayin, and has three taggin, but the right head is rounded like vav, and the bottom right is also rounded since the form is like khaf and vav. Bedeavad, none of this is absolutely crucial [except the part about being hugely bent, which requires elucidation; see the Beur Halakha]. It seems to me that if it was not bent inwards at all it should be shown to a child, but after that it should always be fixed; since it has its form even without being fixed, it doesn’t count as writing out of order. If it was not bent inwards at all and the child didn’t read it as the letter, elucidation is required as to whether it may be amended in tefillin because of writing out of order – see 32:25 on the hump of het; it is possible that the rule is the same here, and the child just isn’t used to seeing a tet which isn’t bent, so we wouldn’t say its form is changed. This requires study. One must take care that the heads of tet not touch each other; see below at the end of letter shin for whether they may be separated by scraping bedeavad if they do touch. If the left head wasn’t like zayin because it was rounded, study is required even if it does have taggin, because of something the Beit Yosef brings below, in the name of the Rambam in the name of the Re-em [R’ Eliezer mi-Mitz – Sefer Yereim] – the gemara says that the letters shaatnez gatz require three ziyunin, which perhaps does not mean taggin but rather means that their heads should not be rounded, but should be extended so that each head has three faces. This could be crucial, as is demonstrated in the Beit Yosef to 36; whether a letter is validated by its taggin or not. One cannot bring proof from the Peri Megadim’s writing that bedeavad they are valid if they don’t resemble zayins, since it is possible that he’s talking about the property of protruding on both sides like zayin, but not about roundness [or lack thereof]; this requires study from the Re-em’s perspective. It is also possible that the halakha here does not follow the Re-em; see 36:15 in the Mishnah Berurah.

The right head is slightly bent inwards, but not hugely bent. The left head resembles zayin, and has three taggin, but the right head is rounded like vav, and the bottom right is also rounded since the form is like khaf and vav. Bedeavad, none of this is absolutely crucial [except the part about being hugely bent, which requires elucidation; see the Beur Halakha]. It seems to me that if it was not bent inwards at all it should be shown to a child, but after that it should always be fixed; since it has its form even without being fixed, it doesn’t count as writing out of order. If it was not bent inwards at all and the child didn’t read it as the letter, elucidation is required as to whether it may be amended in tefillin because of writing out of order – see 32:25 on the hump of het; it is possible that the rule is the same here, and the child just isn’t used to seeing a tet which isn’t bent, so we wouldn’t say its form is changed. This requires study. One must take care that the heads of tet not touch each other; see below at the end of letter shin for whether they may be separated by scraping bedeavad if they do touch. If the left head wasn’t like zayin because it was rounded, study is required even if it does have taggin, because of something the Beit Yosef brings below, in the name of the Rambam in the name of the Re-em [R’ Eliezer mi-Mitz – Sefer Yereim] – the gemara says that the letters shaatnez gatz require three ziyunin, which perhaps does not mean taggin but rather means that their heads should not be rounded, but should be extended so that each head has three faces. This could be crucial, as is demonstrated in the Beit Yosef to 36; whether a letter is validated by its taggin or not. One cannot bring proof from the Peri Megadim’s writing that bedeavad they are valid if they don’t resemble zayins, since it is possible that he’s talking about the property of protruding on both sides like zayin, but not about roundness [or lack thereof]; this requires study from the Re-em’s perspective. It is also possible that the halakha here does not follow the Re-em; see 36:15 in the Mishnah Berurah.

Yud

Its body should measure one quill’s-width, and no more lest it appear like reish. It should be written straight – that is, its head and its face should be level – its face should not be tilted upwards. Lekhathilah it should be rounded on the upper right side. One gives it a leg on the right, and bends the leg towards the left side; the leg should be straight, and not long such that it would appear like vav and be invalidated by a child’s reading. The yud must have a little tag on top, on its face, and a little prickle opposite it, descending. The prickle should be smaller than the tag, and it must be shorter than the right leg, lest it appear like het; if the prickle is so long that it ends up level with the right leg and looks like het it is invaid, and one cannot scrape back the prickle until it is appropriately short because that would be hak tokhot. Rather, he must scrape the whole prickle, and then go back and write it properly. A child’s reading does not help in this case [this is brought in Mishnat Avraham in the name of the Beit Yehudah, and the Le-David Emet, and the Maasei Rokeah, and Kinat Soferim 12]. This only applies to sifrei Torah, not to tefillin and mezuzot, since it would be writing out of order. There is one who writes that according to R’ Y. Akhsandarni [which is brought in the Beit Yosef, s.v. Ve-zeh lashon ha Ria”s nimtza be-ha-Rambam], whose opinion we follow, it is also necessary to scrape off the whole of the right leg and rewrite it [this too, ibid.] [Responsa Beit Yehudah, sec. 74, and the Pithei Teshuvah in Yoreh Deah 274:6]. See the Beur Halakha, where we explain that it is proper to be stringent in accordance with this position. If the yuds in a sefer Torah are like little lameds, it is invalid; the whole letter must be erased and a new yud written, since anything else would be hak tokhot. If such yuds are in the Name, the sheet must be replaced – but if the yuds really are lameds and everyone would see that, one may scrape them even if they are in the Name, until only the body of the dot remains so that one can then add ink at top and bottom to make yud [Responsa of the Hatam Sofer, sec. 269]. Accordingly, one should be extremely careful to mind what the Barukh she-Amar said: that the points should be little and thin so as not to ruin the yud – see there – since if the upper tag is big it will look like a little lamed, and if the lower prickle is long it will look like het. For our many sins there are scribes who are not at all careful about this; they add, as above, or else they don’t do enough, not making any prickle at all on the left side. Really most posekim rule like Rabeinu Tam, that the left prickle is crucial just like the right leg, except that bedeavad they are different: the left side may be amended in tefillin and mezuzot without causing problems of writing out of order but the right side may not, as we explained in chapter 32. The Peri Megadim protested this in his time also. Therefore, one must be extremely careful neither to omit from them nor add to them, as the left prickle should just be a little dot – or very slightly more – coming out of the body of the yud, as is proven from Sefer ha-Terumah.

Its body should measure one quill’s-width, and no more lest it appear like reish. It should be written straight – that is, its head and its face should be level – its face should not be tilted upwards. Lekhathilah it should be rounded on the upper right side. One gives it a leg on the right, and bends the leg towards the left side; the leg should be straight, and not long such that it would appear like vav and be invalidated by a child’s reading. The yud must have a little tag on top, on its face, and a little prickle opposite it, descending. The prickle should be smaller than the tag, and it must be shorter than the right leg, lest it appear like het; if the prickle is so long that it ends up level with the right leg and looks like het it is invaid, and one cannot scrape back the prickle until it is appropriately short because that would be hak tokhot. Rather, he must scrape the whole prickle, and then go back and write it properly. A child’s reading does not help in this case [this is brought in Mishnat Avraham in the name of the Beit Yehudah, and the Le-David Emet, and the Maasei Rokeah, and Kinat Soferim 12]. This only applies to sifrei Torah, not to tefillin and mezuzot, since it would be writing out of order. There is one who writes that according to R’ Y. Akhsandarni [which is brought in the Beit Yosef, s.v. Ve-zeh lashon ha Ria”s nimtza be-ha-Rambam], whose opinion we follow, it is also necessary to scrape off the whole of the right leg and rewrite it [this too, ibid.] [Responsa Beit Yehudah, sec. 74, and the Pithei Teshuvah in Yoreh Deah 274:6]. See the Beur Halakha, where we explain that it is proper to be stringent in accordance with this position. If the yuds in a sefer Torah are like little lameds, it is invalid; the whole letter must be erased and a new yud written, since anything else would be hak tokhot. If such yuds are in the Name, the sheet must be replaced – but if the yuds really are lameds and everyone would see that, one may scrape them even if they are in the Name, until only the body of the dot remains so that one can then add ink at top and bottom to make yud [Responsa of the Hatam Sofer, sec. 269]. Accordingly, one should be extremely careful to mind what the Barukh she-Amar said: that the points should be little and thin so as not to ruin the yud – see there – since if the upper tag is big it will look like a little lamed, and if the lower prickle is long it will look like het. For our many sins there are scribes who are not at all careful about this; they add, as above, or else they don’t do enough, not making any prickle at all on the left side. Really most posekim rule like Rabeinu Tam, that the left prickle is crucial just like the right leg, except that bedeavad they are different: the left side may be amended in tefillin and mezuzot without causing problems of writing out of order but the right side may not, as we explained in chapter 32. The Peri Megadim protested this in his time also. Therefore, one must be extremely careful neither to omit from them nor add to them, as the left prickle should just be a little dot – or very slightly more – coming out of the body of the yud, as is proven from Sefer ha-Terumah.

Khaf, bent

It should be rounded behind, so as not to look like beit, and its behind should be rounded on both sides. The blank space inside should measure at least a quill’s-width. Its upper and lower faces should be level. One should take care that its length not be lessened such that it looks like bent nun to a child (who is neither especially bright nor especially dull) [see the Beit Yosef, in vav of the second alef-bet]. If one made a corner at the back, at the top or at the bottom, it is invalid. There are those who are lenient if the corner is at the top since it is rounded at the bottom, but since this is a d’oraita affair one must be stringent, like the first position, and rule it invalid. Amending it by scraping doesn’t help, since that would be hak tokhot; rather, he must add ink to make it round, provided he hadn’t written any more letters, as that would make it writing out of order. In this case, where there is a corner at the top but it is rounded at the bottom, it is possible that if a child read it correctly it can in fact be said to have its form, and would be able to be amended as above even if he had written on after it, with no problems of writing out of order; see above, 32:25.

It should be rounded behind, so as not to look like beit, and its behind should be rounded on both sides. The blank space inside should measure at least a quill’s-width. Its upper and lower faces should be level. One should take care that its length not be lessened such that it looks like bent nun to a child (who is neither especially bright nor especially dull) [see the Beit Yosef, in vav of the second alef-bet]. If one made a corner at the back, at the top or at the bottom, it is invalid. There are those who are lenient if the corner is at the top since it is rounded at the bottom, but since this is a d’oraita affair one must be stringent, like the first position, and rule it invalid. Amending it by scraping doesn’t help, since that would be hak tokhot; rather, he must add ink to make it round, provided he hadn’t written any more letters, as that would make it writing out of order. In this case, where there is a corner at the top but it is rounded at the bottom, it is possible that if a child read it correctly it can in fact be said to have its form, and would be able to be amended as above even if he had written on after it, with no problems of writing out of order; see above, 32:25.

Khaf, straight

Its leg should be long and its roof short, so as not to resemble reish, although the roof should not be too short, because then it might look like a long vav or like straight nun, and a child’s reading it as such would invalidate it. Accordingly, at the end of a line one may not stretch it to make it long at all. In general one should not stretch letters, but this is because that’s the nice way to do it and bedeavad they aren’t invalid; if one extends the roof of straight khaf so that it looks like reish it is invalid. If it is ambiguous one shows it to a child who is neither especially bright nor especially dull. The leg should be twice as long as the roof, such that if it were bent round it would be bent khaf, since there is no difference between the straight and bent form save that one is straight and one is bent; lekhathilah the sofer should be extremely careful about this because there are those who are stringent and say that this invalidates even bedeavad [Taz, Yoreh Deah 273, see there; he calls such soferim ignorami and says their sifrei Torah are invalid]. This applies to all the straight letters: lekhathilah they should be twice as long as the roof, for this reason. Bedeavad, if one found a stretched straight-khaf in a sefer Torah which looked like reish, and it was possible to extend the leg a little, he should so extend it, but if not, he must erase the whole letter and rewrite it. There are some who are lenient and say it is sufficient to erase only the leg or the roof, but one cannot scrape the roof back until it is an appropriate length, because this is hak tokhot. The sofer must also take care that he does not make a corner on the top of straight khaf; it must be rounded like reish, so that if it were bent over it would be bent khaf. If he made a corner at the top like dalet, it is invalid, and the whole thing must be erased and rewritten, or he may add ink to make it rounded. One may add ink thus even in tefillin and mezuzot; it doesn’t count as writing out of order because it was straight khaf before being amended (as is explained above, 32:25). But if one found this during Torah reading, it is not necessary to bring another Torah, since there are those who declare it valid [see the Peri Megadim to 143 and Derekh ha-Hayim in the laws of Torah reading, explaining that if posekim don’t agree one needn’t bring another sefer]. For all the repeated letters of the alef-bet, one writes the first form at the beginning and in the middle of words, and the other form at the end; if one did it differently it is invalid.

Its leg should be long and its roof short, so as not to resemble reish, although the roof should not be too short, because then it might look like a long vav or like straight nun, and a child’s reading it as such would invalidate it. Accordingly, at the end of a line one may not stretch it to make it long at all. In general one should not stretch letters, but this is because that’s the nice way to do it and bedeavad they aren’t invalid; if one extends the roof of straight khaf so that it looks like reish it is invalid. If it is ambiguous one shows it to a child who is neither especially bright nor especially dull. The leg should be twice as long as the roof, such that if it were bent round it would be bent khaf, since there is no difference between the straight and bent form save that one is straight and one is bent; lekhathilah the sofer should be extremely careful about this because there are those who are stringent and say that this invalidates even bedeavad [Taz, Yoreh Deah 273, see there; he calls such soferim ignorami and says their sifrei Torah are invalid]. This applies to all the straight letters: lekhathilah they should be twice as long as the roof, for this reason. Bedeavad, if one found a stretched straight-khaf in a sefer Torah which looked like reish, and it was possible to extend the leg a little, he should so extend it, but if not, he must erase the whole letter and rewrite it. There are some who are lenient and say it is sufficient to erase only the leg or the roof, but one cannot scrape the roof back until it is an appropriate length, because this is hak tokhot. The sofer must also take care that he does not make a corner on the top of straight khaf; it must be rounded like reish, so that if it were bent over it would be bent khaf. If he made a corner at the top like dalet, it is invalid, and the whole thing must be erased and rewritten, or he may add ink to make it rounded. One may add ink thus even in tefillin and mezuzot; it doesn’t count as writing out of order because it was straight khaf before being amended (as is explained above, 32:25). But if one found this during Torah reading, it is not necessary to bring another Torah, since there are those who declare it valid [see the Peri Megadim to 143 and Derekh ha-Hayim in the laws of Torah reading, explaining that if posekim don’t agree one needn’t bring another sefer]. For all the repeated letters of the alef-bet, one writes the first form at the beginning and in the middle of words, and the other form at the end; if one did it differently it is invalid.

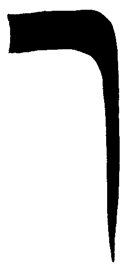

Lamed

Its neck should be long like vav, and the head of the neck should be rounded on the top right and squared on the left, as if it were the head of vav. This is because the shape of lamed is like bent khaf with a vav on top, and for this reason the leg is rounded behind on the right and well bent over to the front, like bent khaf. There are varying views among the posekim as to whether it is necessary to continue the lower line of the khaf so that it is level with the upper line; some say that it is necessary [Radba”z 82, Torat Hayim on Helek] and some say that one need continue it only a little way [Kohelet Yaakov, at the end in the responsa, see there: he writes that he also heard this in the name of the Gra-with-an-aleph]. The custom of scribes is to follow this opinion; see the Beur Halakha. On the left side where the khaf joins to the vav, it should make a corner and not be rounded. The join should be thin, since its form is like vav, and vav gets thinner as it goes down; see above in vav.

Its neck should be long like vav, and the head of the neck should be rounded on the top right and squared on the left, as if it were the head of vav. This is because the shape of lamed is like bent khaf with a vav on top, and for this reason the leg is rounded behind on the right and well bent over to the front, like bent khaf. There are varying views among the posekim as to whether it is necessary to continue the lower line of the khaf so that it is level with the upper line; some say that it is necessary [Radba”z 82, Torat Hayim on Helek] and some say that one need continue it only a little way [Kohelet Yaakov, at the end in the responsa, see there: he writes that he also heard this in the name of the Gra-with-an-aleph]. The custom of scribes is to follow this opinion; see the Beur Halakha. On the left side where the khaf joins to the vav, it should make a corner and not be rounded. The join should be thin, since its form is like vav, and vav gets thinner as it goes down; see above in vav.

He should write the head and the neck bent over a little bit towards the front, and on the head of the neck he should make two taggin, a large one on the right and a small one on the left. All this is lekhathilah, except that some posekim say if he made the neck like a yud it is invalid even bedeavad [see the responsa Or Yisrael, where different opinions may be found; see also Avodat ha-Yom and Le-David Emet]. Accordingly, the sofer should be extremely careful about this. This is the wording of the Barukh She-Amar, to oppose ignorant scribes who shorten the neck of lamed and make a sort of yud on the lamed because they didn’t leave a line’s-width of space between the lines, etc., as the Rokeah wrote explicitly that one must write a vav on the lamed and not a yud. This I found in a gloss to Get Pashut, etc., and so wrote Rabeinu Simha in the name of the Hasid; see there. I have also seen ignorant scribes who, when they accidentally write kuf instead of lamed, first make a neck on top so that it is lamed, and scrape the leg later after the ink has dried – and likewise, if they accidentally write lamed instead of kuf, they write in the leg of kuf and scrape the neck later. This is most certainly invalid, just like a hey in place of a dalet, as we explained above under dalet. If one found a lamed that had just a straight line on top, like this [printed lamed!] – not a vav – one may rule it valid in very pressing circumstances. That is, if one found it on Shabbat a new sefer Torah need not be brought, and in the week it should be fixed, and in tefillin, if he has no others he may lay them without a berakha [Sefer ha-Hayyim, Keset ha-Sofer].

Mem, open

Its form is a bit like khaf plus vav, and so the top right corner should be rounded. But the bottom has a corner, and no heel. The roof above should be level, not rounded – it is only rounded on the right side. The roof shoujld be as long as the base below; all this is lekhathilah. One must be careful to stick the snout on the left to the roof. Lekhathilah it extends level with the roof, except for a little cleft which goes upwards between them. The snout has the form of a vav, standing slightly slanted, but not too much, and it goes down so that it is level with the base, including the base itself. One must be very careful that it should not touch it, but at the same time lekhathilah there should not be too large a gap between them, so that the vav should not be too slanted. If the snout doesn’t join with the roof above, and it looks like khaf and vav, it is invalid, and fixing it doesn’t help in tefillin and mezuzah if he had already written on because it would be writing out of order; as above 32:25, and see the Mishnah Berurah. This is also the rule if the snout joins at the bottom, in the opening of the mem – it is invalid, and we have a ruling in 32:18 about how to fix it, in tefillin and mezuzot provided one hadn’t already written on.

Its form is a bit like khaf plus vav, and so the top right corner should be rounded. But the bottom has a corner, and no heel. The roof above should be level, not rounded – it is only rounded on the right side. The roof shoujld be as long as the base below; all this is lekhathilah. One must be careful to stick the snout on the left to the roof. Lekhathilah it extends level with the roof, except for a little cleft which goes upwards between them. The snout has the form of a vav, standing slightly slanted, but not too much, and it goes down so that it is level with the base, including the base itself. One must be very careful that it should not touch it, but at the same time lekhathilah there should not be too large a gap between them, so that the vav should not be too slanted. If the snout doesn’t join with the roof above, and it looks like khaf and vav, it is invalid, and fixing it doesn’t help in tefillin and mezuzah if he had already written on because it would be writing out of order; as above 32:25, and see the Mishnah Berurah. This is also the rule if the snout joins at the bottom, in the opening of the mem – it is invalid, and we have a ruling in 32:18 about how to fix it, in tefillin and mezuzot provided one hadn’t already written on.

Mem, closed

Closed mem should lekhathilah be rounded on the top right, and squared on the bottom on the left and the right so as not to resemble samekh. If one did not do this, and a child read it as samekh, it is invalid. The Peri Megadim wrote that is better to make it entirely squared, since it is easy to go wrong and make it samekh. This mem must be closed on all sides. Lekhathilah its roof extends outside the enclosure a little bit, like the head of a vav. One should not extend the roof a great deal to the left, and bedeavad one scrapes the excess and it doesn’t count as hak tokhot or writing out of order. If it was found in a Name, there is nothing to be done; it is valid left as it is. On Shabbat one need not bring another sefer Torah on account of this.

Closed mem should lekhathilah be rounded on the top right, and squared on the bottom on the left and the right so as not to resemble samekh. If one did not do this, and a child read it as samekh, it is invalid. The Peri Megadim wrote that is better to make it entirely squared, since it is easy to go wrong and make it samekh. This mem must be closed on all sides. Lekhathilah its roof extends outside the enclosure a little bit, like the head of a vav. One should not extend the roof a great deal to the left, and bedeavad one scrapes the excess and it doesn’t count as hak tokhot or writing out of order. If it was found in a Name, there is nothing to be done; it is valid left as it is. On Shabbat one need not bring another sefer Torah on account of this.

Nun, bent

The head of bent nun is made like zayin, with three taggin on it. It should be no wider than the head of a zayin, so that it should not look like beit, were the head a little wider. For this same reason the base is stretched well over to the left, further than the head, so that it should not look like beit or khaf. The neck, drawn from the middle of the head, is lekhathilah on the thick side, and on the long side, and well over to the right, so as to be able to put another letter next to its head. Lekhathilah nun is rounded on its bottom right. If a bent nun looked like a vav on top – that is, the neck was drawn out from the edge of the head – the Peri Megadim left it undecided in the need for further study, and R’ Akiva Eiger cited this in his novellae. From the Nahalat David (23) it seems that it is valid bedeavad [and in my humble opinion this can also be deduced from the Levush, since when he finishes describing his letter forms, he goes back over the crucial points for each letter, and this one he left out]. In any case, it seems clear that even according to the Peri Megadim it may be amended, even in tefillin and mezuzot, by first scraping away a little of the head on the left side – but not too much, so that the form of nun is retained – and then adding ink to the right side to make the head like zayin. It is not sufficient to add ink to the right side of the head alone, since then the head would be wider than the head of zayin, and one may not do this, as we saw above. See also the Beur Halakha.

The head of bent nun is made like zayin, with three taggin on it. It should be no wider than the head of a zayin, so that it should not look like beit, were the head a little wider. For this same reason the base is stretched well over to the left, further than the head, so that it should not look like beit or khaf. The neck, drawn from the middle of the head, is lekhathilah on the thick side, and on the long side, and well over to the right, so as to be able to put another letter next to its head. Lekhathilah nun is rounded on its bottom right. If a bent nun looked like a vav on top – that is, the neck was drawn out from the edge of the head – the Peri Megadim left it undecided in the need for further study, and R’ Akiva Eiger cited this in his novellae. From the Nahalat David (23) it seems that it is valid bedeavad [and in my humble opinion this can also be deduced from the Levush, since when he finishes describing his letter forms, he goes back over the crucial points for each letter, and this one he left out]. In any case, it seems clear that even according to the Peri Megadim it may be amended, even in tefillin and mezuzot, by first scraping away a little of the head on the left side – but not too much, so that the form of nun is retained – and then adding ink to the right side to make the head like zayin. It is not sufficient to add ink to the right side of the head alone, since then the head would be wider than the head of zayin, and one may not do this, as we saw above. See also the Beur Halakha.

Nun, straight

Its form is like a zayin, with three taggin on its head, but it is long, such that one could make bent nun out of it if it were bent round – that is, not less than four quill’s-widths including the roof. If one made it shorter, he shows it to a child who is neither especially bright nor especially dull, and if he reads it as zayin it is invalid. If he drew the long line out from the end of the roof and made it like vav, the Peri Megadim left it undecided in the need for further study, but the rest of the ahronim [Sha-ar Ephraim 81, Gan ha-Melekh, Le-David Emet] rule that it is invalid.

Its form is like a zayin, with three taggin on its head, but it is long, such that one could make bent nun out of it if it were bent round – that is, not less than four quill’s-widths including the roof. If one made it shorter, he shows it to a child who is neither especially bright nor especially dull, and if he reads it as zayin it is invalid. If he drew the long line out from the end of the roof and made it like vav, the Peri Megadim left it undecided in the need for further study, but the rest of the ahronim [Sha-ar Ephraim 81, Gan ha-Melekh, Le-David Emet] rule that it is invalid.

Samekh

Samekh should be long on top – that is, its roof should be level lekhathilah, and below its base should be short, as it must be rounded on three corners, i.e. the top right and both bottom left and bottom right. It must be completely closed, and lekhathilah the roof on the left side protrudes outwards, like the roof of vav.

Samekh should be long on top – that is, its roof should be level lekhathilah, and below its base should be short, as it must be rounded on three corners, i.e. the top right and both bottom left and bottom right. It must be completely closed, and lekhathilah the roof on the left side protrudes outwards, like the roof of vav.

Ayin

The first mark is like a yud, and lekhathilah its face is tilted a little upwards. Its body is drawn out underneath it, quite upright (since if it is drawn very slanted one won’t be able to put another letter in close to the ayin, should he need to). Inside it there is a zayin, standing straight and touching the leg in its lower half. The head of the zayin should have three taggin. See above, at the end of letter aleph, regarding what happens if the heads touch at more than the appropriate place. One must take great care that the heads do not touch each other, and bedeavad if they do touch each other by as much as a hair’s-breadth, see what we wrote below at the end of letter shin.

The first mark is like a yud, and lekhathilah its face is tilted a little upwards. Its body is drawn out underneath it, quite upright (since if it is drawn very slanted one won’t be able to put another letter in close to the ayin, should he need to). Inside it there is a zayin, standing straight and touching the leg in its lower half. The head of the zayin should have three taggin. See above, at the end of letter aleph, regarding what happens if the heads touch at more than the appropriate place. One must take great care that the heads do not touch each other, and bedeavad if they do touch each other by as much as a hair’s-breadth, see what we wrote below at the end of letter shin.

Peh, bent

Lekhathilah bent peh’s upper right side is a corner on the inside, and on the outside it is also like a little corner. It is drawn a little towards the back, so that it is rounded on the outside. Likewise, below it is rounded on the outside, like all the bent letters which are rounded on the bottom lekhathilah. But inside it should have a corner, so that the white space has the form of a bet. It should be a quill’s-width and a half wide, so as to be able to fit the inside dot in without having it touch the letter’s body. [Gloss: Not like some scribes, who make an external heel in the side /image/ and say that this is to emphasise the white beit within, because this is definitely a broken letter. Truly, it must be rounded without, as we have written, and there needs only to be a white beit within. They do it like this because they don’t know the trick to doing it – that is, to hold the quill at an angle and inside, draw the quill a bit towards the back of the letter; this is what makes the inside corner, as explained in the Beit Yosef – and so they developed the bad practice of making a heel on the outside. They are also in the habit of making a little extension from the end of the roof, and they make the dot with a corner, not rounded – they completely spoil the vav. Thus far was a summary of the relevant part of the Ketivah Tamah. And if one doesn’t know how to do it as per the Ketivah Tamah, it’s certainly preferable that he make the internal beit without a heel, just squared, rather than make a peh which is broken on the outside; since the heel isn’t a crucial feature at all even of a real beit, and so certainly isn’t here, when the heel isn’t even mentioned by the Beit Shemuel, and so one definitely shouldn’t make the peh broken on its account.] It should have a prickle on the left-hand side of its face, which should descend to the dot, the dot being hung from it so that the dot and the continuation of the prickle together would have the form of a vav, were the peh to be inverted. For this reason the dot should be rounded on the bottom left, like the head of vav. The dot should not touch the inside at any place, and if it does it is invalid. One should also take great care that the dot not be turned towards the outside, and even bedeavad its validity requires further consideration. If the dot was not hung from the prickle which is on the face of the peh, and was at some distance inwards from the end of the roof, its status is questionable, and the ruling is as for a hey whose left leg was at the middle of the roof, as explained above in letter hey. If the dot didn’t touch the roof and a child read it as peh, it may be fixed, even in tefillin and mezuzot, as explained in 32:25, see there. If one didn’t make a dot but only a straight line – see above at the end of letter alef.

Lekhathilah bent peh’s upper right side is a corner on the inside, and on the outside it is also like a little corner. It is drawn a little towards the back, so that it is rounded on the outside. Likewise, below it is rounded on the outside, like all the bent letters which are rounded on the bottom lekhathilah. But inside it should have a corner, so that the white space has the form of a bet. It should be a quill’s-width and a half wide, so as to be able to fit the inside dot in without having it touch the letter’s body. [Gloss: Not like some scribes, who make an external heel in the side /image/ and say that this is to emphasise the white beit within, because this is definitely a broken letter. Truly, it must be rounded without, as we have written, and there needs only to be a white beit within. They do it like this because they don’t know the trick to doing it – that is, to hold the quill at an angle and inside, draw the quill a bit towards the back of the letter; this is what makes the inside corner, as explained in the Beit Yosef – and so they developed the bad practice of making a heel on the outside. They are also in the habit of making a little extension from the end of the roof, and they make the dot with a corner, not rounded – they completely spoil the vav. Thus far was a summary of the relevant part of the Ketivah Tamah. And if one doesn’t know how to do it as per the Ketivah Tamah, it’s certainly preferable that he make the internal beit without a heel, just squared, rather than make a peh which is broken on the outside; since the heel isn’t a crucial feature at all even of a real beit, and so certainly isn’t here, when the heel isn’t even mentioned by the Beit Shemuel, and so one definitely shouldn’t make the peh broken on its account.] It should have a prickle on the left-hand side of its face, which should descend to the dot, the dot being hung from it so that the dot and the continuation of the prickle together would have the form of a vav, were the peh to be inverted. For this reason the dot should be rounded on the bottom left, like the head of vav. The dot should not touch the inside at any place, and if it does it is invalid. One should also take great care that the dot not be turned towards the outside, and even bedeavad its validity requires further consideration. If the dot was not hung from the prickle which is on the face of the peh, and was at some distance inwards from the end of the roof, its status is questionable, and the ruling is as for a hey whose left leg was at the middle of the roof, as explained above in letter hey. If the dot didn’t touch the roof and a child read it as peh, it may be fixed, even in tefillin and mezuzot, as explained in 32:25, see there. If one didn’t make a dot but only a straight line – see above at the end of letter alef.

Peh, straight

Lekhathilah one makes it with a corner on top, just like the bent one has on top. Also, lekhathilah it should be sufficiently long that it could make bent peh if it was bent round; bedeavad if the right leg went down as far as the dot and was at least the size of a yud, it is sufficient. [The Peri Megadim writes just that as much as a yud is required from the leg, and he means what we have written, since otherwise it wouldn’t have the form of a letter.] In any case, if one found this in a sefer Torah, and even in tefillin, lekhathilah he is definitely obliged to amend the letter, completing it as per the rule. This doesn’t constitute writing out of order, since it is valid without alteration. The dot and the prickle are all made as for bent peh. One should take care that the dot is not turned outwards, so that it will not appear like tav. If the dot didn’t touch the roof, or was too far inwards from the end of the roof, the rule is as we have stated for bent peh.

Lekhathilah one makes it with a corner on top, just like the bent one has on top. Also, lekhathilah it should be sufficiently long that it could make bent peh if it was bent round; bedeavad if the right leg went down as far as the dot and was at least the size of a yud, it is sufficient. [The Peri Megadim writes just that as much as a yud is required from the leg, and he means what we have written, since otherwise it wouldn’t have the form of a letter.] In any case, if one found this in a sefer Torah, and even in tefillin, lekhathilah he is definitely obliged to amend the letter, completing it as per the rule. This doesn’t constitute writing out of order, since it is valid without alteration. The dot and the prickle are all made as for bent peh. One should take care that the dot is not turned outwards, so that it will not appear like tav. If the dot didn’t touch the roof, or was too far inwards from the end of the roof, the rule is as we have stated for bent peh.

Tzaddi, bent

Bent tzaddi resembles a bent nun with a yud on its back. The first head, the one on the right which looks like a yud, has its face tilted upwards a little. The leg of the yud is well stuck to the neck of the tzaddi, and one should take great care that it be joined in the middle of the neck, not at the bottom, so that it not resemble ayin. The second head is like a zayin, protruding from each side; one should not draw the neck out from the end of the head, but from the middle, as for nun, above. The neck should be rather thick, and rather long, stretched over to the right side so as to be able to fit another letter in next to its head. Its lower base is lekhathilah drawn well over to the left side, further than the two heads, and lekhathilah it should be rounded below on the right, like all the bent letters. It has three taggin on its left head. If the yud doesn’t touch the nun, see 32:25. If the heads touch more than at the place where they are joined, so that there is only a straight line – the head isn’t discernible – see above at the end of letter alef. One must take great care that the heads do not touch each other; bedeavad see what is written at the end of letter shin.

Bent tzaddi resembles a bent nun with a yud on its back. The first head, the one on the right which looks like a yud, has its face tilted upwards a little. The leg of the yud is well stuck to the neck of the tzaddi, and one should take great care that it be joined in the middle of the neck, not at the bottom, so that it not resemble ayin. The second head is like a zayin, protruding from each side; one should not draw the neck out from the end of the head, but from the middle, as for nun, above. The neck should be rather thick, and rather long, stretched over to the right side so as to be able to fit another letter in next to its head. Its lower base is lekhathilah drawn well over to the left side, further than the two heads, and lekhathilah it should be rounded below on the right, like all the bent letters. It has three taggin on its left head. If the yud doesn’t touch the nun, see 32:25. If the heads touch more than at the place where they are joined, so that there is only a straight line – the head isn’t discernible – see above at the end of letter alef. One must take great care that the heads do not touch each other; bedeavad see what is written at the end of letter shin.

Tzaddi, straight

The heads of straight tzaddi are as for bent tzaddi. It is also composed of a yud and a nun, but the nun is a straight nun, and therefore its body is straight like straight nun. Lekhathilah, the minimum length below the part where the heads join should be long enough to make bent tzaddi; bedeavad the Peri Megadim says that if there is only as much as a yud below the place where the yud joins the nun, it is valid, but if there is not as much as a yud it requires investigation. If the heads touch more than at the place where they are joined on, or if they touch each other, or if there is a break between the yud and the nun, it is as for the bent form, above.

The heads of straight tzaddi are as for bent tzaddi. It is also composed of a yud and a nun, but the nun is a straight nun, and therefore its body is straight like straight nun. Lekhathilah, the minimum length below the part where the heads join should be long enough to make bent tzaddi; bedeavad the Peri Megadim says that if there is only as much as a yud below the place where the yud joins the nun, it is valid, but if there is not as much as a yud it requires investigation. If the heads touch more than at the place where they are joined on, or if they touch each other, or if there is a break between the yud and the nun, it is as for the bent form, above.

Kuf

Kuf’s roof should be level, and lekhathilah it should have a little tag at the front of the roof at the left side. The prickle should be thin, so as not to spoil the form of the kuf – that is, one could say that this makes it look like a lamed. The Maasei Rokeah wrote that for this reason, one should set the tag back from the end of the roof; see there. Its right leg must be well bent underneath towards the left leg, like bent khaf, but it should be much shorter than the roof. The left leg is suspended in it. It has the form of a straight nun, but rather shorter, and accordingly its head should be thick and it should get thinner as it goes along, like nun. Lekhathilah, one should not put it further than the thickness of the roof away from the roof; lekhathilah, one should draw the suspended left leg on a slight diagonal to the right. One must take great care that the leg not touch the roof or the leg next to it. Also, one ought not to put it too close to the roof; there should be a gap between it and the roof such that it is clearly discernible to the average person reading from a sefer Torah on the bima. The leg should not be opposite the middle of the roof, but at the end, on the left side. If the leg touches the roof – also for the leg at its side – or if one made the leg at the middle of the roof, all the rules are as for letter hey, as we have explained above in letter hey. If the left leg is only as long as a yud, from the bent part and below, it is valid bedeavad [the Peri Megadim wrote of kuf – s.v.קי”ל ניקב רגל הה”א… קו”ף רי”ש – he finishes: If there remains of the right leg…and it seems to me that he meant this to apply to the rest of the letters].

Kuf’s roof should be level, and lekhathilah it should have a little tag at the front of the roof at the left side. The prickle should be thin, so as not to spoil the form of the kuf – that is, one could say that this makes it look like a lamed. The Maasei Rokeah wrote that for this reason, one should set the tag back from the end of the roof; see there. Its right leg must be well bent underneath towards the left leg, like bent khaf, but it should be much shorter than the roof. The left leg is suspended in it. It has the form of a straight nun, but rather shorter, and accordingly its head should be thick and it should get thinner as it goes along, like nun. Lekhathilah, one should not put it further than the thickness of the roof away from the roof; lekhathilah, one should draw the suspended left leg on a slight diagonal to the right. One must take great care that the leg not touch the roof or the leg next to it. Also, one ought not to put it too close to the roof; there should be a gap between it and the roof such that it is clearly discernible to the average person reading from a sefer Torah on the bima. The leg should not be opposite the middle of the roof, but at the end, on the left side. If the leg touches the roof – also for the leg at its side – or if one made the leg at the middle of the roof, all the rules are as for letter hey, as we have explained above in letter hey. If the left leg is only as long as a yud, from the bent part and below, it is valid bedeavad [the Peri Megadim wrote of kuf – s.v.קי”ל ניקב רגל הה”א… קו”ף רי”ש – he finishes: If there remains of the right leg…and it seems to me that he meant this to apply to the rest of the letters].

Reish

Lekhathilah reish’s roof should be level, and one must take great care that it be actually rounded behind, so that it not appear like dalet. If it appears like dalet, it is invalid, and if one isn’t sure, one shows it to a child. Its leg should be short, so that it not appear like straight khaf, and its roof should be long, like the length of beit, so that it not appear like vav. Bedeavad, if there is a doubt one shows it to a child, as above. If one made the leg of reish as short as yud, it is sufficient bedeavad – Peri Megadim – and see below at the end of letter tav.

Lekhathilah reish’s roof should be level, and one must take great care that it be actually rounded behind, so that it not appear like dalet. If it appears like dalet, it is invalid, and if one isn’t sure, one shows it to a child. Its leg should be short, so that it not appear like straight khaf, and its roof should be long, like the length of beit, so that it not appear like vav. Bedeavad, if there is a doubt one shows it to a child, as above. If one made the leg of reish as short as yud, it is sufficient bedeavad – Peri Megadim – and see below at the end of letter tav.

Shin

Shin has three heads. The first head, with the leg which is drawn out of it, is like a vav, and its face is tilted slightly upwards. The second head is like yud; its head is tilted slightly upwards, and lekhathilah it has a little prickle on it. The third head must be made like zayin, and it has three taggin on it. The left heads of all the letters שעטנז גץ are like zayin. One must take care that the heads do not touch each other. The leg of this left head should lekhathilah be particularly vertical, and one draws the leg from the first head down towards it at an angle, to its point. The leg of the second head is also drawn inclined below, to the left, until the three heads come together in one at the bottom. If the middle yud doesn’t touch at the bottom, the rule is explained in 32:25; see there. The base of the shin should not be wide nor rounded, but pointed. Then all the three heads will stand at the bottom on one leg, like kuf and reish. Bedeavad, if the base of shin is wide, the Peri Megadim leaves the case in need of investigation. If one wrote shin with four heads it is invalid, and it is not sufficient to scrape away one head, since this is hak tokhot. Rather, one must invalidate the letter and complete it. In tefillin and mezuzot, if one had written on after it, fixing doesn’t help, because it is writing out of order. [Peri Hadash, Even ha-Ezer; Peri Megadim, introduction; Le-David Emet; other ahronim. This is not like the Maharika”sh.] If there is a break at one of the heads, the rule is explained in 32:25. If one of the heads touches more than just where it is joined, so that there is only a straight line – the head isn’t discernible – it is invalid, and a child doesn’t help. If the heads touch each other, even by a hair’s-breadth, it is invalid. Regarding fixing, see the Mishnat Avraham, who writes that most posekim hold that scraping works here, since we don’t say that the form of the letter was thereby changed, it was just deficient because it wasn’t surrounded by blank klaf at that place, so subsequent scraping works. It seems otherwise to me; since there are many posekim who are stringent, we should only be lenient in tefillin and mezuzot if one had written on after, as it would count as writing out of order. This is not so for a sefer Torah, in which one should invalidate the form of the letter and complete it.